Contemporary history The exhibition "Unsuspended Nazi Justice" caused a sensation 60 years ago - at a time when hardly anyone in post-war Germany thought about reappraisal. | By Stefan Jehle

Karlsruhe's Ludwigsplatz is only 200 meters from the Federal Court of Justice and 400 meters from the Federal Constitutional Court. On the edge is a building that was built in Munich's Art Nouveau architecture at the beginning of the First World War - and in which for a long time only Munich beer was served. The restaurant was called the crocodile. In the Weimar period, personalities such as Gustav Stresemann or Winifred Wagner were said to have been guests here several times, according to the Karlsruhe City Archives.

At the end of 1959, the restaurant, which today mainly serves tapas and tacos from Mexican cuisine, was an exhibition venue for three days: dozens of notebooks with files on the Nazi criminal justice system were on the inn tables at noon and had to be used again before the restaurant started in the evening be cleared. They caused violent discussions among the German public, as hardly anyone in the post-war years thought of dealing with the outrageous crimes of the Nazi regime. Not only the “Black Forest Messenger”, but also our newspaper, the “Frankfurter Allgemeine” and even the “Times” and the “Guardian” reported on the unusual exhibition.

Originally, the show was not supposed to be shown in a restaurant, but in the town hall. A group of Berlin students, registered at the Free University and belonging to the Socialist German Student Union (SDS), had booked a small hall in the event complex. Karlsruhe was chosen as the seat of the highest German courts for the premiere of the traveling exhibition. But in the town hall it was over after an evening. "At the pressure of Bonn's ministries," Reinhard Strecker recalls, the city council had buckled. The students had to move their exhibits to the crocodile.

Press conference lasting several hours

Strecker, who was the initiator of the exhibition and enrolled at the FU for the exotic-looking study of Indo-European languages, will soon be 90 years old - but his memories are unclouded. “At the time, the pressure of the defamation from Bonn was great enough that the city declared the rental agreement to us null and void,” he says. But in the end Strecker was even grateful to the ministerials afterwards: The Bonn Federal Press Office had been inadvertently helpful. The agency would have "sent all national and international journalists to Karlsruhe" because it hoped to report against the exhibition.

But this plan didn't work. The first day of the exhibition in the crocodile began with a press conference lasting several hours and detailed explanations by the students about the exhibition. For the first time, the actions of Nazi death judges were publicly denounced - actions by lawyers who had issued questionable judgments during the twelve years of Nazi rule and who were still active in German courts in the then young Federal Republic.

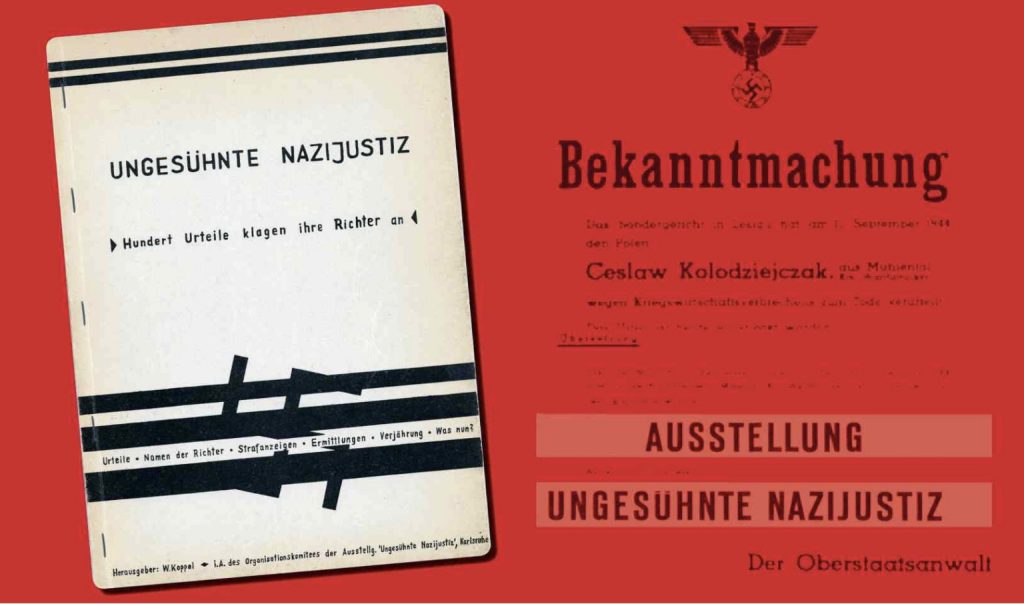

The exhibition, entitled “Unspeaked Nazi Justice”, consisted almost exclusively of quick-release folders that were used by the authorities at that time. A total of 105 death sentences, some of them highly questionable, were listed in the files, which, according to the research of Strecker and his fellow students, involved 206 judges and prosecutors during the war. This brought the issue to the public's attention almost 20 years before the Filbinger case triggered a political earthquake in southwest Germany.

The lawyers who were deemed to be burdened named the students by name, place of residence and the professional position exercised in 1959. Denounced in this way were, for example, a district court director from Tübingen, a district court councilor from Hechingen as well as a Federal Supreme Court judge and a public prosecutor from the federal prosecutor's office in Karlsruhe.

Two months later, in January 1960, Strecker and his colleague Wolfgang Koppel filed a criminal complaint against 43 former Nazi judges in office on behalf of the SDS federal executive board “on suspicion of legal evasion in manslaughter”.

According to Strecker, the press conference on November 28, 1959 at the Krokodil inn was “characterized by an emotionally aroused atmosphere”. The next day, with very few exceptions, "there were only positive reports" across the German press. The exhibition, which was shown a little later in Berlin, Tübingen, Hamburg and Munich and in 1961 also in Freiburg and Stuttgart, was before the Frankfurt Auschwitz Trials. It was to mark the end of the silence about the National Socialist past.

Supporters and critics

The documents, which were mainly exhibited in seminar rooms, back rooms of restaurants, small art galleries and student dormitories, were not explained in great detail; in individual cases, only handwritten banners were used to explain them. Immediately after Karlsruhe, the show, which ran until 1962, was shown from February 23 to March 7, 1960 in a Berlin gallery on Kurfürstendamm.

In the summer of 1960, the students made several guest appearances in the clubhouse in Tübingen. The exhibition title had been changed to "Documents on Nazi Justice". Again, attempts were repeatedly made to influence the student groups, participating professors and finally the rector of the university - the organization of the exhibition was questioned several times before the show started on July 11, 1960.

The files shown in the clubhouse were photocopies of court records and judgments, judicial and personnel files, some of which were of poor quality, all of which were simply summarized as evidence of the unlawful nature of the Nazi judiciary. Theologians Helmut Gollwitzer and Martin Niemöller and the writer Golo Mann were important advocates for the exhibition organizers.

However, the predominantly benevolent reporting by the media did not change the fact that, for example after the presentations in Karlsruhe and Berlin, three senators from the Governing Senate of West Berlin - the senator for education, the interior and the judiciary, all legal trainees and magistrates instructed in writing To “stay away from machinations in Solde Pankows”. This was an allusion to the suspected weakness of the show: many of the files that Strecker and his colleagues analyzed were photocopies of negotiation protocols and death sentences from previously unpunished Nazi judicial crimes from East Berlin and other Eastern European archives.

Confirmation from the highest authority

Even in parts of the SPD there was a clear defensive stance. It was conjectured that the students were controlled by the Communist GDR leadership. In retrospect, Reinhard Strecker is also convinced of his actions: “At that time we met in my apartment for regular checking and identification of all the people whom we named as the perpetrators, and gradually found more and more hundreds of pages of documents. It was an immense review. ”Everything should be right.

Strecker and his colleagues received confirmation from the highest authority immediately after the Karlsruhe show: The German Federal Attorney General Max Güde (in office from 1956 to 1961) confirmed in an interview with Südwestdeutscher Rundfunk that the documents issued by the student group were authentic and genuine.

Güde, whose then official office was on the area of the Federal Court of Justice only around 200 meters from the exhibition site on Ludwigsplatz, also contradicted the claim that mild judgments in the Third Reich resulted in reprisals against responsible judges. But the highest prosecutor of the Federal Republic also got into the crossfire: he was instructed a little later by the CSU-led Federal Ministry of Justice in Bonn "to stay out of the public debate about the Nazi judicial lawyers in the future". Max Güde moved to the Bundestag in 1961 as a Karlsruhe MP for the CDU.

Reinhard Strecker received late satisfaction: The "student reconnaissance", as the news magazine "Der Spiegel" called him, received high honors at an advanced age. They came late - but not too late: Strecker was awarded the Federal Cross of Merit in 2015. And last fall, Strecker received a certificate of honor for his "special commitment as the initiator of the historical exhibition Unsuspected Nazi Justice" from the SPD regional association Berlin, of which he is a member, despite the temporary hostility from his party - signed by SPD state chief Michael Müller.

The indirect consequences of the traveling exhibition were immense. In 1962, an amendment to the law triggered by the show enabled members of the judiciary who worked during the Nazi era to “retire on request”. With paragraph 116 of the German Judges Act of September 8, 1961, this was made possible for the judges who had been involved in the administration of criminal justice during the war - "leaving their pension payments". It looked like a kind of general amnesty. The Federal Constitutional Court also never wanted to change that. The president at the time was Gebhard Müller, a native of Upper Swabia. He was in office from 1959 to 1971 - with headquarters in the vicinity of the location of the first exhibition "Unsuccessful Nazi Justice" at Karlsruhe's Ludwigsplatz.

Source: Article by Stefan Jehle in the Stuttgarter Zeitung from April 16, 2020